CASE FILE #004 — TROUT LAKE, 1896

Quick Facts

- Region: Trout Lake, Northern Alberta, Canada

- People Involved: Cree / Oji-Cree

- Classification: Wendigo Possession / Cultural Execution

- Primary Witness: Francis Work Beatton (HBC outpost clerk)

- Victim/Subject: A Cree man identified as Napanin

- Outcome: Ritual execution by community

- Status: Unresolved / culturally adjudicated

Introduction — When Winter Devours Men

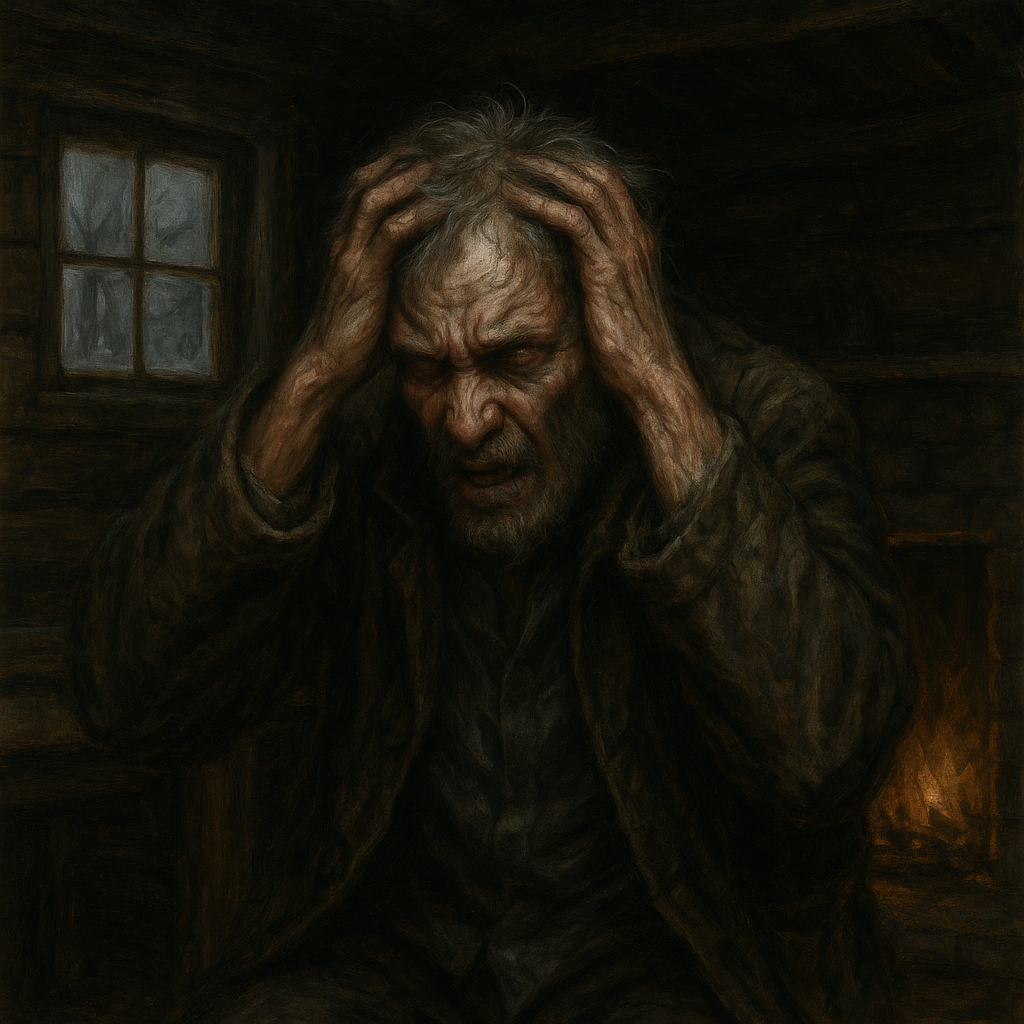

In the winter of 1896, deep in the boreal wilderness of northern Alberta, a man stumbled into the Hudson’s Bay Company outpost at Trout Lake—starved, shaking, and convinced that something ancient was growing inside him.

His words were calm, but his gaze was wild.

He begged the trader to kill him before it was too late.

“My heart is freezing… I do not want to eat my family.”

His plea marked the beginning of one of the most fully documented Wendigo cases on record.

In a land where winter could swallow entire camps without leaving a trace, many disappearances were blamed on starvation, storms… or the Wendigo.

But this time, there was a witness—

and a journal.

Origins — When the Ice Takes the Heart

Among Algonquian-speaking peoples, the Wendigo (wihtikō / windigo) was not always a monstrous forest giant—

it was often a condition.

A sickness of hunger and isolation.

A spiritual frost that seeped into a person’s heart,

drying compassion,

kindling hunger,

and turning them into a danger to everyone they loved.

The Wendigo was both:

- A spirit of endless hunger, and

- The name for those who succumbed to its influence

A person could become Wendigo slowly—

through winter starvation, trauma, or forbidden appetite.

When the heart freezes…

the mind follows.

The Arrival: January 1896

The man later identified as Napanin arrived after days in the snow, nearly incoherent.

Hudson’s Bay clerk Francis Work Beatton recorded his condition in the outpost journal:

- He complained his heart was turning to ice

- He felt an overwhelming urge toward cannibalism

- He believed a spirit shadowed him

- He asked to be killed before he harmed others

He was, by outward appearance, not starving.

There was food nearby.

His body was strong enough to walk.

This only deepened the fear.

Symptoms — “The Ice is Spreading”

Witnesses noted behaviors consistent with traditional signs of Wendigo affliction:

- Uncontrollable dread

- Fear of harming loved ones

- Dreams & visions of a dark visitor

- A sensation of cold growing inside the chest

- Refusal to eat normal food

- Isolation and muttering

- Repeated begging for death

His eyes were said to “follow things no one else could see.”

He trembled as if freezing, though he sat beside the fire.

Nothing warmed him.

The Cure Attempts — Melting the Heart

The Cree community attempted a traditional cure—

a sweat lodge intended to drive the ice from his body.

Inside the heat, he screamed:

“It will not melt! It is inside me!”

He vomited.

He shivered violently even as steam burned his skin.

Afterward, he seemed worse.

He no longer begged for help.

He became quiet.

Calm.

Too calm.

Those who knew the stories recognized this shift.

The ice had reached his heart.

The Execution — A Mercy Killing

When the cure failed, the community did what they believed was necessary:

They chose to end his life before he transformed.

This was not murder.

It was Wendigo execution, a culturally sanctioned act to protect the people.

Napanin did not resist.

He may even have thanked them.

No record names the executioner;

only that the community acted together,

and that the body was treated with care—

to ensure the spirit did not return.

Beatton wrote of the death in stark terms.

To him, it was tragedy.

To the Cree, it was prevention.

Press & Rumor — A Trout Lake Tragedy

Months later, newspapers reported:

“A WENDIGO EXECUTED BY COMPANIONS FOR THEIR OWN SAFETY.”

Headlines sensationalized the event,

capturing the public imagination.

To outsiders it was madness.

To locals, it was necessity.

To historians, it became one of the best-preserved cases of Wendigo belief intersecting with colonial record.

Aftermath — Silence in the Snow

The outpost records fall quiet after the execution.

No follow-up.

No medical report.

No autopsy.

In northern winter, the land buried what remained.

Only the journal stayed behind—

ink on page,

the final record of a man who felt the cold inside take hold.

Local oral tradition says the family mourned deeply.

Some say his spirit still wanders near Trout Lake,

crying out that his heart is frozen.

Interpretation

This event sits at the crossroads of:

- Indigenous spiritual reality

- Extreme winter psychology

- Cultural law

- Colonial documentation

Was it:

- A case of psychosis?

- Trauma-induced delusion?

- A spirit possession?

- A culturally informed mercy killing?

No one can say.

But every worldview agrees on one point:

Once the ice reached his heart, he would not return.

Why This Case Endures

The Trout Lake Incident remains one of the most referenced Wendigo cases because:

- It involved first-hand documentation

- The afflicted requested death

- The community conducted a ritual execution

- Newspapers circulated the story

- It blended Indigenous belief with colonial record

- The event remained unsolved and unchallenged

Unlike sensational tales of antlered giants,

this is a story of human horror—

the terror of losing oneself,

becoming a danger to the people you love most.

Sometimes,

the monster is the hunger within.

Conclusion

The Wendigo is not only a creature of the deep woods—

sometimes it is found sitting by the fire,

shivering,

begging for help.

At Trout Lake in 1896,

one man recognized the darkness forming inside him.

Unable to stop it,

he asked for the only cure left—

an ending.

The community carried the burden,

and winter took the rest.

Today, there is no grave.

No memorial.

Only the entry in a trader’s notebook,

and the warning it still carries:

Even the warmest fire cannot melt certain kinds of ice.

SOURCES

- Journal references attributed to Francis Work Beatton (Hudson’s Bay Company outpost, Trout Lake, 1896)

- Newspaper reporting (1896) commonly summarized under headlines such as:

“A Trout Lake Tragedy — ‘Wendigo’ Killed by His Companions for Their Own Safety.” - Cultural & historical discussion appearing in scholarship by:

- Nathan D. Carlson — analyses of wihtikō / windigo history in the Athabasca region

- Accounts involving the Auger family and oral histories of execution practice

- General ethnographic synthesis from late-19th to early-20th century Cree/Ojibwe accounts of Windigo belief and historical cases